The professional guest speaker at the 2025 Hawaii High School Awards ceremony was Blaze Lovell, an investigative reporter with Civil Beat. Here is audio of his speech and an AI-generated transcript.

I’m really glad to see so many people here today. I was a high school journalist much like many of you, but I I didn’t get to go to the high school journalism awards and never won anything. If there was a award for being the least valuable player, I probably would have won that when I was in high school. So hats off to you all for being so dedicated.

I actually just wrapped up the speech really early this morning. I graduated from high school almost 11 years ago, but it turns out I still haven’t learned to stop procrastinating on things. So there I was last night trying to write this thing. It was late. I’d just wrapped up a big story on how the state lacks its oversight and how it’s been spending millions of dollars on homelessness initiatives. I was tired. My eyes hurt. I really wanted a beer, a hug, and for my cat to love me. What I wanted even more than that was just to sleep. After all, it was after midnight. Doesn’t that sound familiar?

These nights where I’m up late working, they happen more often than you’d think even after all these years on the job. You probably think I’m crazy for still working like I do and if you think that then you’d be correct. After all, in order to get into a career field that’s lost 56% of its workforce since the year 2000, you’ve got to be a little bit nuts. But I am a little bit nuts and at Civil Beat, I’m in good company.

For those of you who don’t know me yet, I’m an investigative reporter at Civil Beat. We’re a nonprofit newsroom dedicated to public affairs reporting and watchdog journalism. Civil Beat launched in 2010 just around the time that the two major papers here were truncating and there was a lot of consolidation in media. That was also the year where I started high school at Pearl City. And once I saw Civil Beat, I knew that that’s where I wanted to work eventually when I grew up. But I didn’t know how to get there.

Growing up, you know, I didn’t see anyone who looked like me in the media. I didn’t really see myself represented anywhere as a matter of fact. So I’m hoping this story helps some of you who, you know, felt like me when I was in high school. You see, I’m a Hawaiian Japanese kid that grew up with a single mother. My earliest memories were being in a nightclub that my parents owned down this dank alleyway in Chinatown. The club always smelled like cigarette smoke. This is back when you could still smoke indoors. The smoke, it sort of just clung to your clothes and stuck in your nostrils long after you left. We sometimes slept in an office above the bar and I remember being cold because the AC was always on too high and trying to fall asleep on the green carpet while we could see the cockroaches crawling around the wall. But most of all I remember my parents fighting, throwing things, shelves falling down, glass cracking, screaming, crying. Sometimes I couldn’t tell if it was one of them that was crying or if that was just me.

I felt trapped, like I’d never get out of there. The club was aptly named Ground Zero and it was like a constant reminder, “Hey kid, here’s where you are. You get to start at rock bottom.” When I got to high school and I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life, most of my friends wanted to go into business or finance,you know, careers where you could make like a boatload money. And so instead I decided to be poor for the rest of my life and be a journalist. No, I’m kidding, I’m kidding.

What I really wanted to do was I wanted to do something that could help make life better for people here. You know, make life better for that little boy being raised by a single mom. But I just didn’t know what that was. I was absolutely awful at math. I hated science, well like not the way the federal government hates science now, like I love science, I just don’t like the subject. I loved reading and writing. My English teacher in junior year, Mrs. Ching, was also my drivers ed instructor and the advisor of our school paper, The Messenger. And she encouraged me to apply there and start writing.

My first story was about how Pearl City High School went into lockdown after a series of fights, which came to be known as the Big Riot. I spent lunch breaks for days interviewing key witnesses and people who were near when the fights broke out. I was trying to figure out who was involved. I talked to the teacher who subdued a student who had picked up a brick like he was about to throw it at somebody. And then when the story published, I royally screwed up and reported that a vice principal was taken to the hospital when in fact he had just received medical attention at the scene and got chewed out by him the next day. It was traumatizing and exhilarating all at once and right there I knew what my life’s path was. It was all set up before me. So I decided to major in journalism in college.

I initially got into Washington State University but I had two major problems. I didn’t like cows and I didn’t want to live on a farm. And so I decided that I should be in a bigger city, you know where news actually happens. And so I ended up enrolling in the University at Nevada, Las Vegas. I worked at the school paper, which was then called the Rebel Yell, where I started as a staff writer and I eventually worked my way up to being a managing editor in charge of the editorial content of our paper. I covered UNLV student government, which let me dip my toe into the world of politics, money, and scandal.

I also covered the Nevada Board of Regents where I learned how to comb over reams of documents while looking for stories and competed with the daily newspaper reporters in the valley on various construction fiascos involving UNLV. There were a lot of late nights spent writing and rewriting. I also worked on our coverage of the October 1st, 2017, mass shooting in Las Vegas that left more than 58 people dead. Those experiences all helped prepare me for the quote unquote real world.

Throughout college I’d been applying for summer internships with Civil Beat through the Society of Professional Journalists summer program. But the first time I got rejected, so I had to go back to my lifeguarding gig in Kapolei. But the summer after, I got in on my second try and I got two offers that year. One was from the Star Advertiser which said they paid me eight bucks an hour. The other was from Civil Beat which said they’d pay 12. So, that was the easiest decision I’ve made in my entire life.

Uh plus the guy who called me from Civil Beat said they had a foosball table and free coffee. We get to pau hana at the end of the week. I was sold. That summer at Civil Beat gave me a preview of what the rest of my career would look like. Pitching stories, trying to dig deeper, going through intense edits. I returned to UNLV to finish my degree and got lucky enough to be invited back to Civil Beat for a yearlong fellowship that eventually turned into, well, I just never really went away. I kind of just stuck around there.

On my first day back that day in 2018, I remember my mentor, Nick Grube, told me, “Welcome to the first day of the rest of your life.” You’d think I felt like I made it at that point, but even then, it’d be years before I actually felt like I knew what I was doing. Still, I picked up some things along the way, so here’s the part of the speech where I give you some practical advice. If you’re college bound, be sure to find your student newspapers. They always need writers and you certainly need to practice.

Write as much and as often as you can, ideally on deadline, like turning around a story in a few hours, not a few days or weeks. And always read, never stop learning because that’s really all reporting is, is going to bed at night, knowing more than you did when you woke up in the morning. Try to lean into the things that you might think are boring. Yeah, you know, it’s not fun to sit through like a really long education board meeting or to try to read through gigantic 500-page documents.

But it’s important work, and you need to learn how to translate all that into something that people can understand and that people care about. Start thinking of documents and data as sources just as much as you do people because people can lie to you, but paper never can. And I wish someone had told me how to start using spreadsheets when I was in high school because it took me years and years of working in the professional field to figure this out. I used to add stuff up on notebook paper and now you can do that in like 20 seconds with a spreadsheet. It’s amazing, what computers can do, kids.

But I won’t sugarcoat things for you. The outlook in journalism is bleak. The pipeline I was able to take advantage of is fading. There are less student media publications at the high school level that can get students interested in journalism than there were 20 years ago. Similarly, many college publications have struggled to stay afloat. I know that firsthand after having to secure funding for my college paper year after year.

Resources at legacy media are dwindling as is funding for summer internship programs. If you’re like me and you went to a public school the stats are stacked against you. If you’re a person of color like many of you in this room doubly so. I went to a journalism conference last year and at one of the panel presentations they showed the racial breakdown of the conference’s membership on the screen. Of the 1,800 members who reported their race in membership profiles just one was native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. And so I looked around the room eagerly seeing who else it was until I realized that that one person was me.

The task in front of us is daunting, but that’s why I’m encouraged to look out on all of you today and know that we still have a future here for local journalism. I thought about the theme of this of how journalists change the world. I don’t want you to think that you need to change the world all at once.

Let your work change the world of one person, one community, one small step at a time. For me, that step came two years ago when I went to work for the New York Times. I spent a year on an investigation into campaign contributions from people who win government contracts. Some of that has figured prominently in recent corruption scandals. Right now, lawmakers are using that reporting as fuel to push through reform measures aimed at eliminating public corruption here in Hawaii. That’s a major change we rarely see in Hawaii politics.

After that story ran, I felt like I finally made it. Like I finally belong in this world that wasn’t made for me. But that reporting, as in-depth as it was, it won’t solve homelessness, it won’t bring down the cost of living, or solve the plight of our female athletes, or solve our state’s intractable economic problems. Those are all stories for another day, something for all you to take up if you so choose. If you choose to embrace all the cliches of journalism that I and my colleagues believe in wholeheartedly, that it’s a duty to shine light in dark corners, to hold power to account, to put their feet to the flame, to comfort the afflicted and to afflict the comfortable, to balance the scales against all that’s old and evil in this world. if you can change even a small part of the world, I hope eventually you’ll find that it’ll change you.

My friends wanted to go out for a night one time recently in Chinatown. We eventually ended up down this dank alleyway where the smell of old cigarette smoke still lingered. I found myself outside of my parents’ old bar. We sat down, ordered some drinks and talked for a while. The walls were still chipped in most of the same places. The bathroom stalls are just as creepy as they were before, but one thing was different. When it was time to leave, I had the freedom to get up and go wherever I wanted.

Thank you, folks.

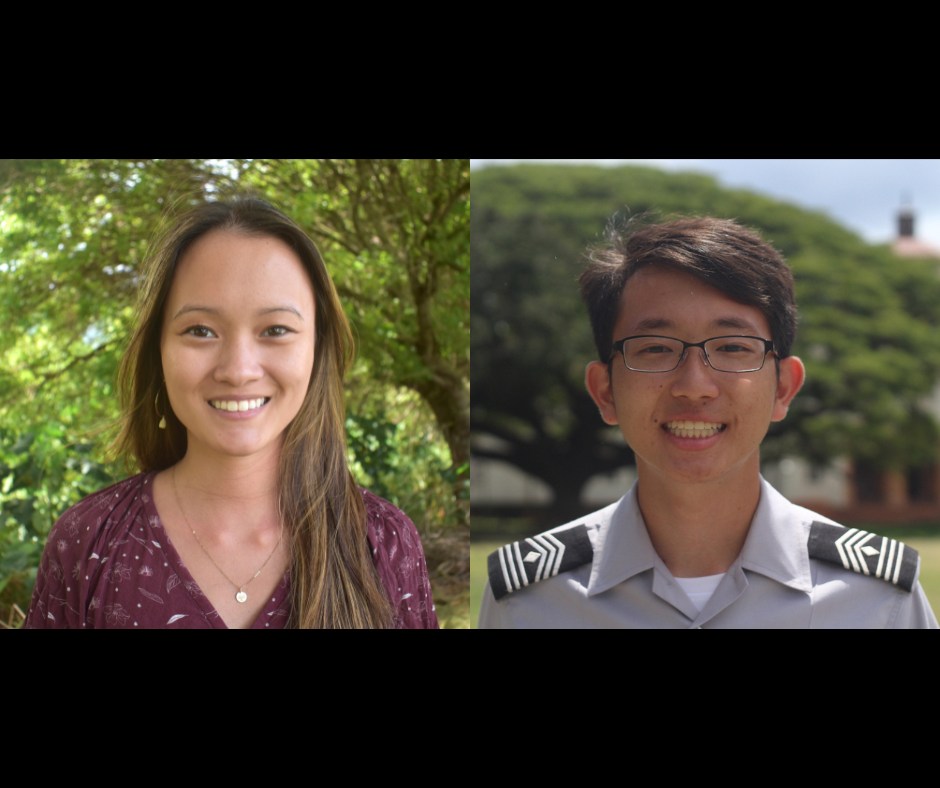

Kaelyn Pacpaco, Hawaii’s 2025 Journalist of the Year, gave the student address.

I wasn’t supposed to be part of my school publication, Imua.

As a ninth grader filling out my elective form, I ranked “Imua Newsroom” dead last, somewhere below Ceramics and Photography. So when it showed up on my schedule, I was more than a little surprised. I mean, how unlucky did I have to be to land my very last choice?

Still, I climbed three flights of stairs to the newsroom with zero journalism experience, zero expectations, and, if I’m being honest, zero clue what I was doing. At the time, it was overwhelming to be thrown into something so unfamiliar. But looking back now, it was one of the most important, happy accidents of my life.

My first article was on “Bees for Breast Cancer,” a student-led initiative. I remember obsessing over the formatting, unsure if I’d conducted the interview correctly, and being terrified of making a mistake. But when the issue came out and I saw my name in print—for the first time—it was surreal. People I barely knew mentioned reading it, and I realized then that this wasn’t just a class assignment. It was something real. Something with reach. With impact.

As student journalists, we hold one of the most unique responsibilities imaginable. Our work may seem fleeting, just another article, another issue, another news cycle, but it’s more than that. News often feels like it fades in and out, only relevant for a brief moment. But the truth is, we are not just reacting to the present. We are recording it. We are actively writing history.

We capture the firsts—the moments that matter to our school communities. This year, Imua covered student perspectives on our school’s new phone ban, the construction of a long-awaited student center, and the first-ever girls flag football season. I have no doubt that your publications also captured meaningful “firsts” within your own school. Because we’re all part of something bigger than ourselves. We’re documenting the voices of our generation. And that’s an incredible responsibility to carry.

It’s a responsibility I carried with deep pride this year as Imua celebrated its 100th volume. One hundred volumes. Over a century of student voices, editors, staffers, and advisers, each leaving their mark, each helping to shape a living, breathing legacy. It was truly humbling to be part of that.

But our vision for Volume 100 wasn’t just to celebrate the milestone. It was to understand it. To honor the students who came before us, and to recognize the footsteps we were following. To achieve this, I spent hours in the archives, surrounded by brittle paper and faded photographs. I read first hand student accounts of the World War II era and stumbled upon passionate editorials debating U.S. intervention in Vietnam. I learned how students before me interacted with the world around them, and how they used journalism to make sense of the chaos.

And while I don’t plan to study journalism in college, the lessons it’s given me are permanent. Journalism taught me how to be curious about everything. How to find interest in any topic I’m writing about. It taught me how to write, to design, to communicate, and, most importantly, how to connect with people. These are skills I will carry into every part of my future, wherever it takes me.

In a meeting with a former Imua adviser for an article I was writing, he handed me something unexpected: a string ball. It was made from all the string once used to bundle newspapers since the 1970s. He called it “the tangled web of high school journalism.” And honestly, I think we can all relate. The late nights, the layout disasters, the interviews that didn’t go as planned. It’s messy. But it’s also meaningful.

I later discovered a 1998 article that shared its story: the adviser had been taught never to waste a single piece of string. Over time, no one quite knew what to do with it. But today, it sits in our newsroom, a reminder that we’re forever connected to the advisers, staffers, and stories who came before us.

So to all the student journalists here today: keep writing. Keep digging. Keep asking tough questions. And while you’re at it, look back. Talk to the former staffers. Revisit the dusty archives. Find out who wrote before you and why. Because understanding our past gives weight to the work we’re doing now, and makes our stories stronger. Journalism is the first draft of history, and you are all part of writing it. Thank you so much, and congratulations to everyone here today.